Hot on its heels. Patrick Leclezio tracks the local response to the global gin explosion.

First published in Prestige Magazine (February 2016 edition).

If there was even a slight hint of doubt about how searingly hot gin has become in the last few years it would be persuasively quelled by the extent of the local craft gin industry. I’d set out late last year with preparations for a review, which I’d hoped would be comprehensive, but my ambitions were thwarted by sheer numbers, and by what seemed like a constant stream of new entrants. My selection was eventually limited to nine, resulting in a mix of the more established, the new, and the brand new – in practical, manageable proportions; but keep in mind that there are a lot of others out there, with more joining by the day. There’s a gin heaven manifesting itself in South Africa and the gates are wide open. Join me for a quick tour.

It can be difficult to make any kind of systematic sense of gin. There are so few objective rules, and so much potential for variation. Juniper is ostensibly intended to be the dominant flavour – the word gin is in fact a derivative of juniper – but this has become doubtful (and somewhat controversial) in recent times, as new gins have been increasingly pushing the boundaries in attempts to carve out distinctive niches for themselves. Resistant purists claim that without the strong juniper a gin is simply a flavoured vodka. It’s a classic conflict between innovation and tradition. In fairness this was a regulation that was crying out of be trampled. How do you legislate flavour? Action may need to be taken though to tighten things up, such is the pace of developments – a subject for another time. Our local legislation is less prescriptive, simply calling for the presence of juniper amongst the botanicals, but not specifying anything further. The result is a whole new style of “African” gins – based on the use of indigenous ingredients – in which juniper is either receded into the background, or in fact entirely undetectable. I’ve had my nose in a big pot of juniper extract on more than one occasion so I’m confident that I’m familiar with its pine-y flavour – enough to identify its reticence. Anyhow, despite this departure, these gins are nonetheless is unmistakeably gin, in the nature and composition of its other botanicals.

The two most long established brands are the well-tractioned Inverroche, which has entrenched itself as the country’s flagship craft gin, and the more reclusive Jorgensen’s. The three variants of the former – Classic, Verdant and Amber – and two variants of the latter – its eponymous gin and saffron gin, were assessed for this review. The Inverroche Classic sets the benchmark for the profile of a fynbos based gin. Its base of cane spirits redistilled with limestone fynbos botanicals imparts peppery and savoury flavours – creating an interesting, edgy drink that’s likely to find favour with those who prefer their gins in the Beefeater mould. Jorgensen’s by comparison has a fuller, richer flavour – with hints of its grape base peeking through. I used it in a martini on whim, yielding impressive results, the only detraction being that it maybe lacks the “sessionability” (the dubious advisability of sessionable martini drinking is noted) of something softer. But that’s a question of personal taste. The other Inverroche variants use different recipes of botanicals, mountain fynbos for Verdant, coastal fynbos for Amber, whatever these might mean, as well as undisclosed fynbos infusions, resulting in gins that are substantially contrasted to the Classic and to each other. Most importantly both combine astoundingly well with tonic – not something that I say lightly. Jorgensen’s Saffron is a more subtle deviation from its parent – likely because the distillate used is the same, or very similar. Distillation is a dark art, one which I don’t pretend to fully understand, but what knowledge I have has made me partial to copper pot distillation – the method used by both Jorgensen’s and Inverroche – as a superior attributor of flavour. Whether this is justified or not it’s a preconception that’s certainly borne out by the well-crafted depth of flavour in these two gins.

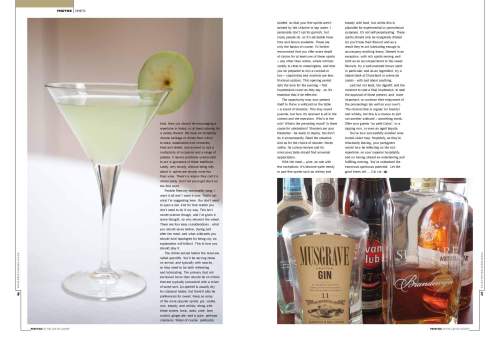

The other bookend comprises newcomers to the scene in the form of Musgrave and Blind Tiger gins, the latter yet-to-be-launched. Musgrave is a bold gin that is African in both theme and flavour. Its broad and pronounced ginger flavour is derived from its use of African ginger as a prominent botanical. Less pronounced but discernible nonetheless is the cardamom – I’m a big fan of spicy tea, so I was particularly pleased with its inclusion. Blind Tiger occupies what seems like a separate space from its local peers, and from the defining local style. It is softer, sweeter, and more classical, more international. It also packs some additional value at 46% ABV, which shouldn’t be overlooked. The in-betweeners are two variants from the Woodstock Gin Company. I found them to be little spirity, with flat flavours, but this may be unfair, especially since they were evaluated alongside more premium priced gins. Apples and oranges. The one is made from barley spirit and the other from a grape spirit – but both from the same recipe, offering fascinating insight into the influence of that base spirit. Worth checking out on that basis alone.

This burgeoning story of local gin is vibrant and inspiring, and hopefully it’ll continue to instil interest and gather momentum. The scene has been set, and the narrative has been populated with an expanding cast of compelling characters – refer to the handy table adjacent for a plot summary. It’s safe to say I’d venture that you can look forward to a persisting and varying injection of quality liquid for your GnT’s and your martinis. May the botanicals be with you.

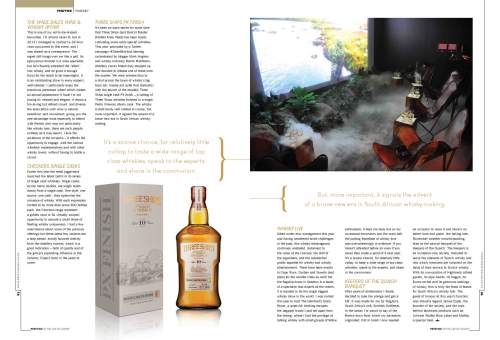

As it appeared – p1.

As it appeared – p2.